Teachers taught, guided, and sometimes fed my sisters and me — be it from the commons of a budget or from their own pockets. I owe them. It wasn’t because my family was absent. My mom, then a student nurse, had few precious hours with us while studying, working, and surviving a system structurally allergic to womxn unfettered from men. Opting into every summer program or after-school club was necessity, not elective.

As she’d study, we’d watch Star Trek during its 90s run. There was an episode where Picard, a ship’s captain, is captured. He’s interrogated and asked how many lights he sees. “Four lights.” The interrogator insists that there are five and tortures him. It’s a scene cribbed directly from Orwell’s 1984, a critique on authoritarianism. However, it’s also an examination of people struggling against larger systems and gaslighting.

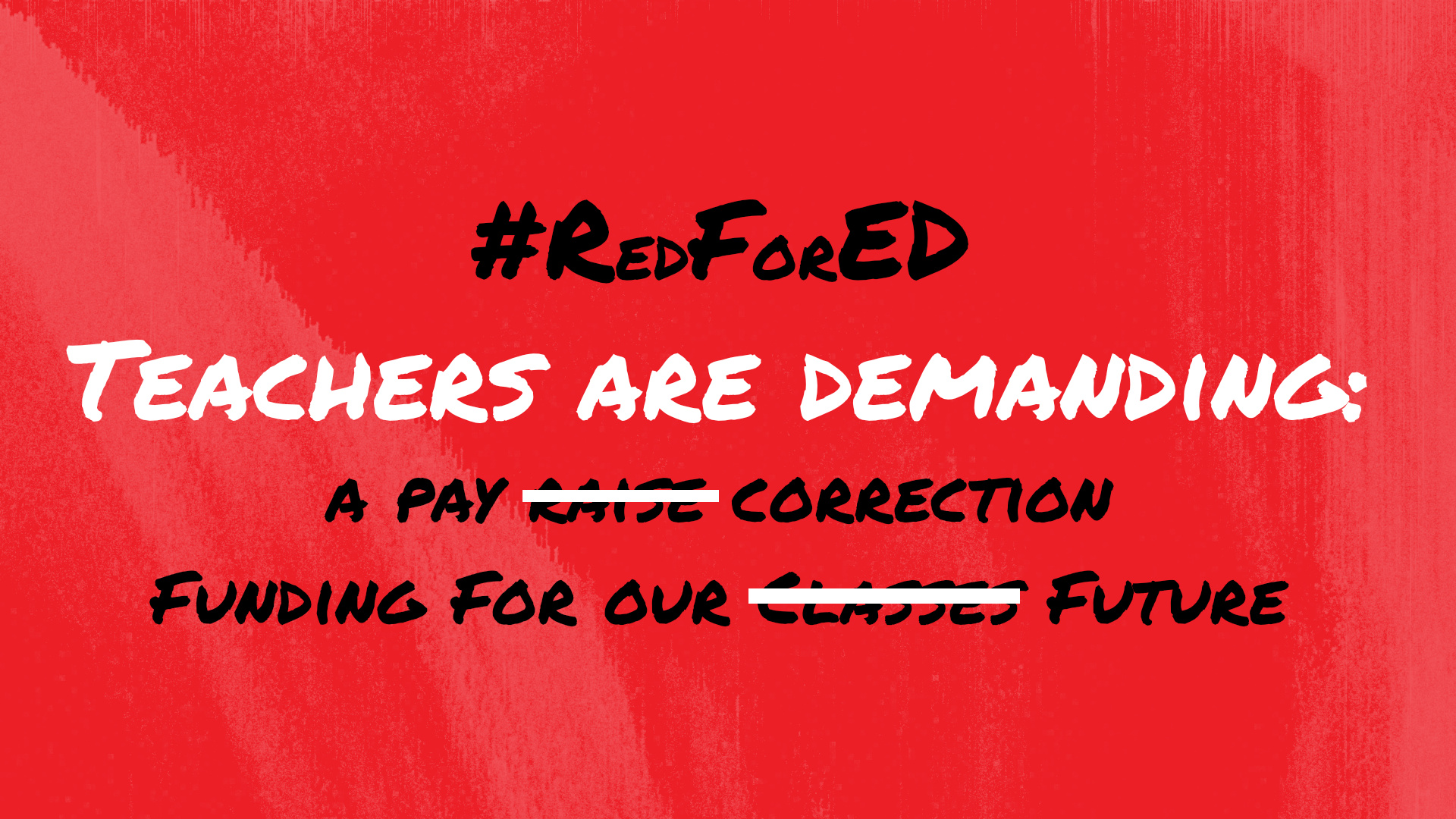

In the context of teacher strikes, teachers know the material conditions they’ve lived on. It’s not theoretical. They know student debt and rent and budget cuts. It’s first hand. It’s lived experience. They know the kids with aching stomachs. Kids who need more at school and, perhaps, more at home too. Management tries to say otherwise. They say pay is “competitive” and that students are met with “wise stewardship of public funds.” The Pasco/Kennewick, Tacoma, and Highline districts present three very different struggles in education and labor activism, of workers reclaiming the dignity they’re always and forever due.

Note: Due to potential backlash from school districts, unions, and reactionaries, the interviewees herein have been given pseudonyms.

Tacoma

I drive my three-year old through the perpetual construction around Tacoma to meet an old friend, Karyn, a teacher in the Tacoma School District. I lift my child out, yellow race car in hand, and we stand in the straw, waist-high grass. Karyn gestures to the yard, “I need to get to this.” It’s 10 am. She asked for red shirts for the picket line. I answered. That Sunday, they hadn’t held the strike vote yet. They were missing the 2/3rds quorum necessary to vote (a percent of all possible teachers and an absurdly high figure). Inside, Karyn offers chalk to my toddler to write on a blackboard-painted wall. A parrot shrieks. My kid, disinterested in chalk, climbs and falls off the low-rise sofa in amusement.

I haven’t seen Karyn in almost six years. Time treated both us well, even if we’re respectively more broke and worn more thin by life than we ever were in college. To give a sense of Karyn, she grew up on pop-punk, Gilmore Girls, and Daria. She still wears gauges. We both wear tattoos. It’s as if six years haven’t passed and I’ve merely re-entered from stage left.

“People complain about buying school supplies on Facebook,” she says, gesturing to a table in front of her. It’s a bounty of what she scrounged from the end of the year. The table is an oversize glass thumbprint, resting atop her departed father’s boot-locker from the military. His name is still etched into the upper-left. Growing up raised by her grandmother, a tough and long-suffering but loving woman, who shaped Karyn just as Karyn shapes students in her classes. Both are dedicated.

Karyn’s budget is $200 per year. For everything. If a used textbook costs $20, that’s ten textbooks. That’s it. That’s what covers all her classes the entire year. Tacoma Schools are some of the lowest paid in the state today. The district once bragged about paying competitive salaries but with the 2011 forward McCleary funding standstill, inflation from a wealthier influx to the region, and a budget shortfall caused by the Democrat’s supposed fix to McCleary that cut into cash-poor districts like Tacoma, talk hasn’t meant much. Mere talk never does. Tacoma is treated as an afterthought by the legislature. Describing this, Karyn winces. I change the subject to the drumstick displayed on the wall adorned with photos of her at a concert. It’s like a punk-rock ofrenda. “Is that Cyrus Booloki’s?” Her eyes light up again.

Karyn is becoming active with the TEA: out of necessity but also “democratic civic duty.” She says this with emphasis, taking on the character of a former teacher and union-organizer, a die-hard from the 1980s, pounding a fist on her outstretched hand like pulpit during a sermon. Despite not being a union member, her fate is as linked to the same collective bargaining agreement as anyone else. In her specialty, children in special education, it’s acute.

“A student made a shiv for me once,” she said, pulling a chipped, obsidian blade wrapped in shoelace from her desk. “It wasn’t a threat, I think.” The workload is challenging but she’s not asking for a handout, just the pay that she’s already due. Her demands are the same as any other teacher in the district. “I’m a single mom. I’ll strike — but it’s nice to eat and have shelter overhead.”

I ask how people can help out. “Call the local Education Association. Post on social media,” she says. “A lot of the press coverage has focused on one side of the story. That side isn’t ours.”

The big conglomerate coverage is eaten up in policy wonks and liberal hand-wringing on “stewardship” on how to spend the McCleary increase. The district is claiming that it’s “needed for a rainy day” and there’s not enough in the budget for teacher pay. Their initial offer was a mere 3% increase, after years of nothing. “To keep up with wages when you and I graduated college,” she says, “we’d need double digits.”

Since talking with Karyn, the Tacoma school districts have been on strike and building resources to feed and provide childcare for families in need, through the week of September 10 at least. Karyn is still worried about a lack of pay during this time but is energized saying, “It’s amazing to be part of something greater than yourself.

“Teachers deserve more respect throughout America. We spend hundreds of dollars of our own money each year on school supplies, spend countless early hours & late nights worrying about the well being of other people’s children while also managing households of our own. Not just September through June but year round while asking for very little in return. We are not superhuman[.] Teachers are people too. A little compassion goes a long way.”

Pasco and Kennewick

Pasco schools’ path diverged in the heart of south-central Washington. Teachers struck in 2014. Maddy, an elementary school teacher, fought “for a raise and curriculum.” It was exhausting but that effort yielded a bountiful harvest this year without a need to walkout: “14% raise, great contract language for special education and training.”

It wasn’t all rosy. Maddy points out lack of language honoring contracts with nurses. “Our school nurses are part of our teacher union contract. There caseloads are high, their previous out of school experience doesn’t count on the pay scale and they don’t receive a classroom budget,” Maddy explains. Using the salary schedule, a Registered Nurse, with eight years experience in a hospital setting, was being paid $36,512 and would only make around $44,114 this year because none of that experience is counted.

Add on to that, these nurses face workloads so large that they carry work home. As one of the Pasco nurses shared with Maddy:

My grandfather, a retired educator in the Kennewick, talked over the West Virginia strikes in late July, bringing cherry tomatoes in from the garden. He’s delighted by all three varieties. They’re growing faster than he can pick in the heat. The inside of the pail is like staring down a sunset. Sun Gold tomatoes are the cat’s pajamas. We both talk about democracy — but at work. He knows districts will be a bind between inequitable funding for years. Despite the McCleary “fix”, many teachers aren’t seeing equity in their pay.

Highline

Dean didn’t start wanting to be a teacher. It was through being a graduate teaching assistant that he found his calling. “I was consistently pulled toward working with students, which was arguably supposed to be my lowest priority behind doing research and succeeding in my own classes […] but I quickly realized that teaching was what I had to be doing.”

Whereas Pasco’s union still carries the experience and energy of organizing in 2014, Highline’s teachers can, at times, butt heads with closed-room deals between Union representatives and district management. The teachers recently vote to strike at a meeting with over 900 people (out of 1400) on August 23.

“Moral was high at the time of the vote. [We] voted 96.7% to authorize a strike,” he offers, admiring the strength of his fellow teachers. “[Yet] the general membership will not see, let alone vote on, the full terms of this agreement until September 12th. We will have access to the TA for up to one hour before voting on whether or not to ratify.”

It highlights a greater issue of transparency for workers around the terms of their contracts and pressure, with school already starting, to simply carry on. Districts are eager to prevent disruption, trying to prevent transparency and communication during what ought to be a democratic process. What’s more the district tries to turn the community on the teachers: “Some small efforts are made toward community and/or family outreach, but these are often too late in the decision-making process to be meaningful. […] Those outreach efforts are simply a box for the district to check, a photo op to publicize, after the real decisions have already been made.

“The decision-making processes seem to be largely held within the district office by administrators who make 2-3 times more than starting certificated teachers, 5-6 times more than some paraeducators and school support staff, and who spend little time in the schools and communities they are supposed to serve. Our school board is largely made up of people who have run unopposed, some for multiple terms, and thus do not feel fully accountable to our community.”

It’s the opposite of a community-led, popular vote between teachers and the community, instead focusing on a few actors. This false division creates tension when schools are so deeply embedded in the care, feeding, nurturing, and education of students. The disconnect between leaders weighs on Dean: “Each year they get less connected to our community, more entrenched in their power, more sure that they know what’s best, and our educators, students, and families are consistently left to do more with less.”

Striking Forward

I’m reminded of those four lights and being told there’s five. Washington State teachers have met ends meet on four. They’re told it’s five. Washington’s teachers deal with our regressive tax system, low pay, oversize classrooms, and grueling testing cycles. Management contributes to this. They extol preserving a bottom line, of wise stewardship (aka austerity).

It’s not just educators; workers everywhere are gaslit like this. As we see with tax cuts for the rich compounding wealth for the wealthy: for stock buybacks, not rank-and-file compensation. US workers are conditioned to feel grateful, even when management coerces them to accept less. “A job’s a job,” some say. It’s quiet. Humiliating. It’s a tinge and a whisper of indignity that workers are asked to concede.

It doesn’t have to be this way. So long as there are human needs left unfulfilled, there will always be jobs and work aplenty to meet those needs. Without worker control of the economy, we can only serve profit of a few, instead of the needs and dignity of the many.

It’s not without hope. As teachers throughout the state win back double-digit pay increases, they’re showing everyone how to fight back but win. It’s a win needed in this day and age.

One comment on “Teachers Striking but Not Struck Out: Four Struggles, One Humanity”

Comments are closed.